A look back to the shaving practices of WW1

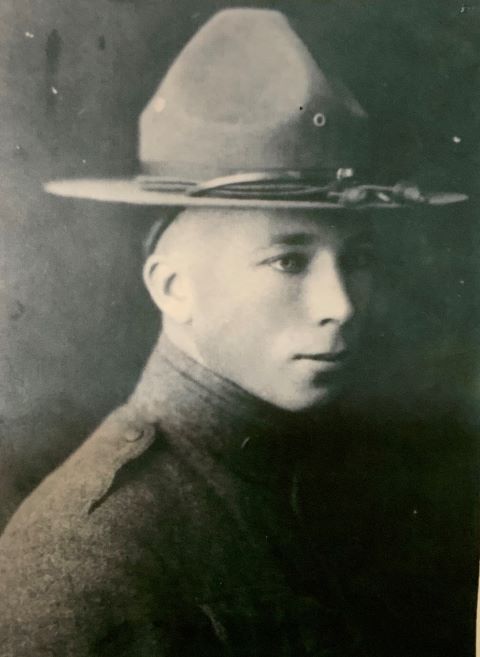

You may remember these photos from previous posts. On the left is my paternal grandfather Emil Johnson, and on the right in the center is my maternal grandfather George Anderson. Today what I would like to point out to you is how cleanshaven they were. Little did I know, there was a reason for that, and it had to do with military regulations.

In the process of what I now refer to as dismantling my childhood home, I came across a collection of men’s razors that looked antique to me.

Naturally the first thing I did was look on Google for visual matches. Sure enough, this one looked like the 1934 Gillette Safety Razor. Wow! Selling on eBay for $99. That was pretty cool.

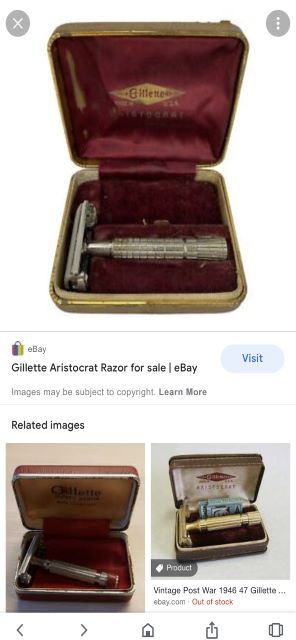

I found out that this one was the Gillette Aristocrat Razor, but I didn’t get a screenshot of the price. The bottom left razor, marked “Out of Stock” was from 1946-47 (Post WW2) but it’s a little different so they year might not be the same as mine.

But by far the most interesting was this one, that said “Property U.S. Army” on the back. Where would the Johnson family have picked up something like this? Obviously more research was in order.

It wasn’t long before I had found this info online. It made sense to me that being cleanshaven would have helped gas masks to fit more tightly, and also that shaving could prevent lice.

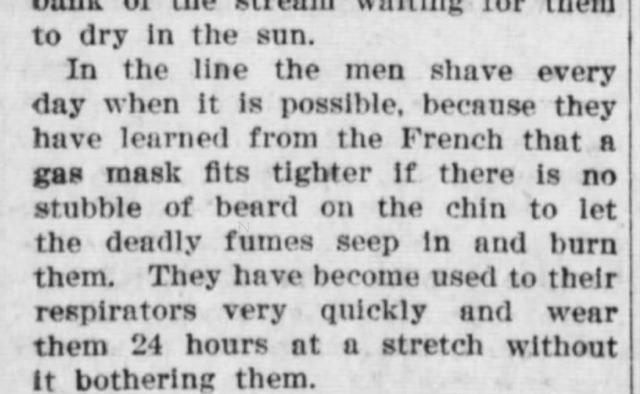

In an article published in a Michigan paper in 1918, we read that the French had learned that gas masks fit more tightly if the soldier was cleanshaven.

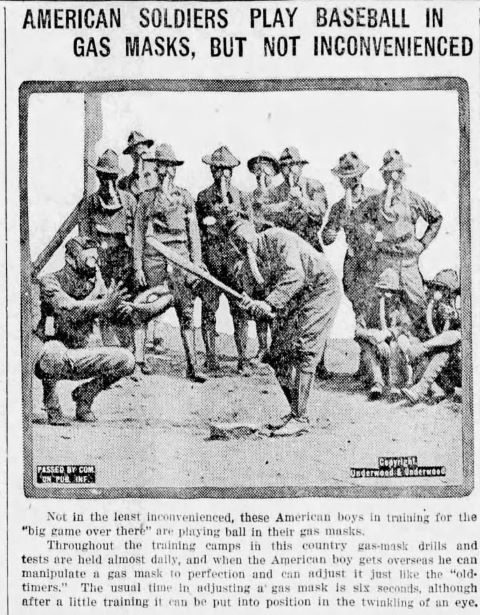

I admit to being a bit skeptical as to whether the troops could really “wear their gas masks for 24 hours without it bothering them”, but maybe they could, if this 1918 article from Chicago is to be believed.

It follows, then, that the razor I had found was most likely from a “Khaki set” that Grandpa Johnson had received sometime during World War 1. Unfortunately, I’ve only found the razor, not the box. I did see this intact khaki set on eBay for $250.

Based on photos I found online, the serial number is on the other side of the piece that says, “Property U.S. Army”. You have to twist the handle to remove it. Because I can’t get mine off, I can’t see if it has the “J” serial number mentioned above, but I have seen them advertised as having a “G” serial number as well. I’m going to guess that as long as a razor was inscribed with “Property U.S. Army”, it came from a khaki set.

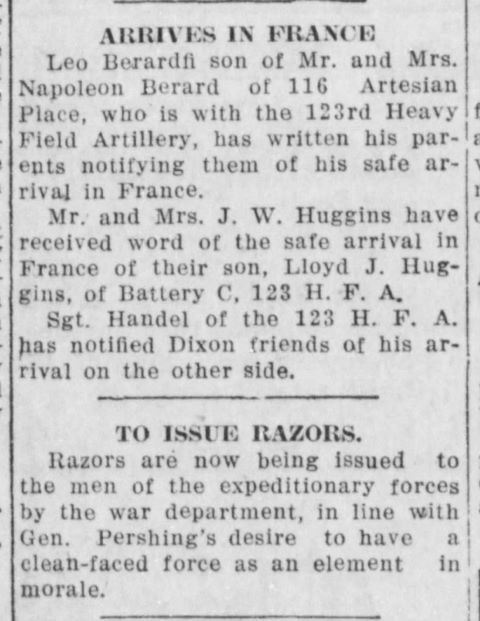

Interestingly enough, in this June 15, 1918, clipping from Dixon, Illinois, members of the 123rd Heavy Field Artillery, to which Emil belonged, had sent word of their safe arrival in France. Immediately below is a blurb about razors being issued by the war department “as an element in morale”.

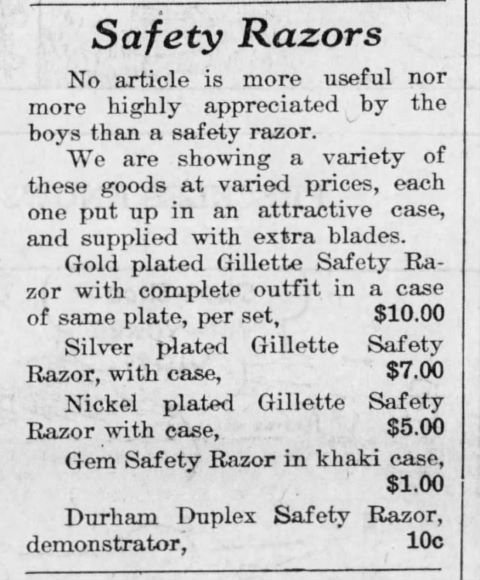

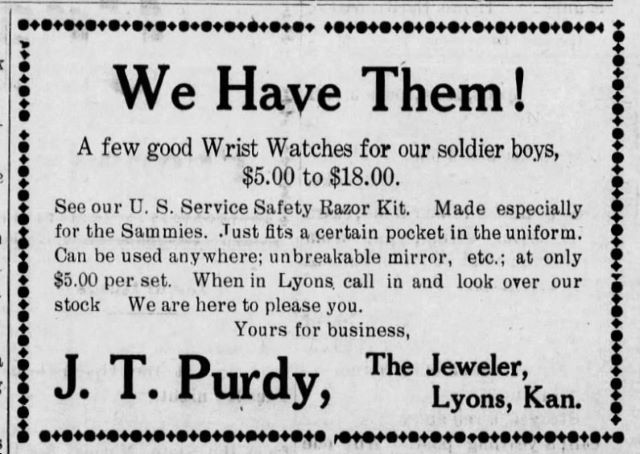

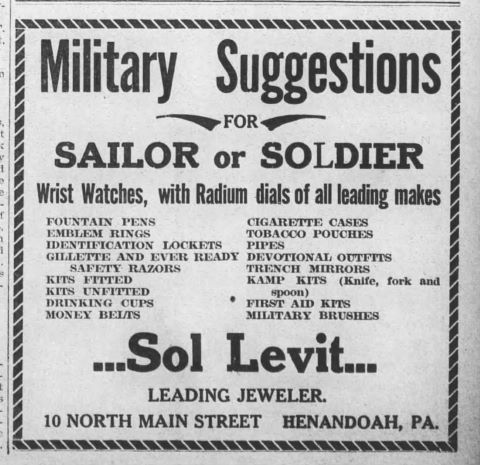

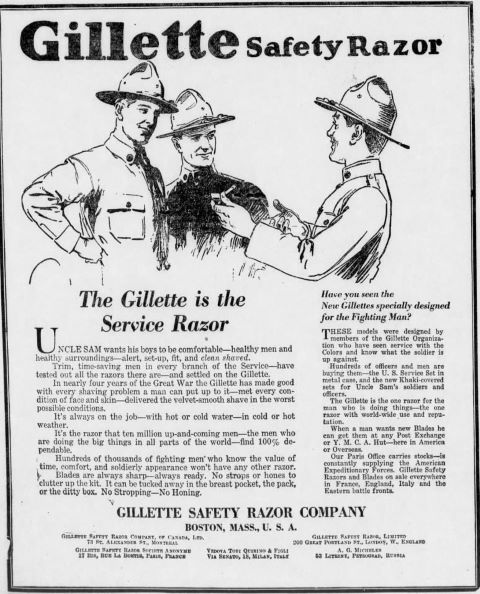

As we might imagine, shaving kits quickly became popular gifts for the soldiers overseas. The Khaki sets were given by the Army to the troops, but the ones available for purchase in stores came in a metal case. In this ad, we see that “safety razors and trench mirrors are of the utmost importance to a soldier as the U.S. government demands the American soldier to be clean shaven”.

Interested to see what $10 in 1918 would be in today’s economy, I looked it up here, and the answer was $203.83!

I was surprised to see that in addition to shaving kits, small compact Kodak cameras were popular gifts for soldiers. Like the shaving kits they were adapted to fit into the soldiers’ uniforms. That must be where so many of those tiny military photos came from.

This is from an article in the Lynn, Massachusetts “Daily Evening Item”. Dated June 16, 1919, it tells that 266 safety razor kits, “appropriately inscribed”, were presented to the “boys entering the service”, while the women joining the military received gold rings bearing the seal of the town. The money used for this had been appropriated in 1917, two years earlier. Notice the reference to the two influenza epidemics at the end.

At that time, information from letters sent by service men was often published in the local papers so everyone could be kept current on their friends and relatives overseas. In this article we are told that Leon Ricker of the 102nd machine gun battalion was pleased to receive his razor kit from home, and so was Lieut. Robert Johnson (no relation).

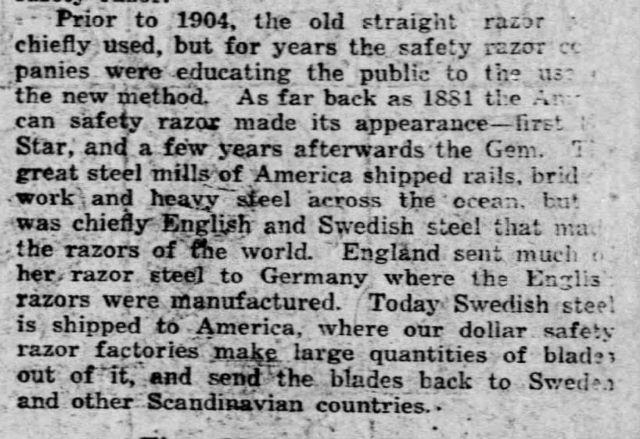

I found it especially interesting that many of the American safety razors were made from imported Swedish steel. This is from a December, 1919 article by Clive Marshall which was quite extensive and was really about the history of shaving in general, not just during the war. If you want to read the whole thing, click here.

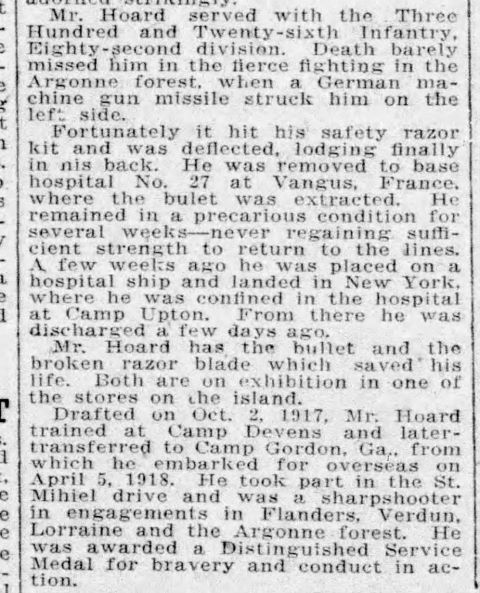

This article came from a Connecticut paper in 1919. At the right is an enlarged excerpt describing how a razor kit deflected a bullet, ultimately saving soldier George Hoard’s life.

I looked for information on whether the other branches of service were required to shave, but I couldn’t find anything definitive. I do know that the few Navy photos I have of my grandfather George show him as cleanshaven.

In my research I was able to find this website from the UK, which has a fascinating information and photos on the subject of shaving and cleanliness in the trenches during WW1. I’m assuming I can share this picture here, since on the site its creator is listed as unknown.

So now you know (almost) everything anyone could want to know about shaving during the first world war. I myself would like to learn more, but if I waited until then, this post would never get finished.

Love this blogpost!

Thanks😀

Wow interesting history. Thanks for sharing 😊

Glad you liked it!😀

How interesting! I learnt so much from this blog post – fascinating with all the old clippings and photos! I imagine people would have had to save up quite a bit to afford razors if they were that expemsive…

Thank you! Yes I found the info

interesting too. A lot of things I never knew before!

I found this post very interesting, and learnt a great deal reading! I love all the old clippings and photos. I imagine people would have had to save up quite a bit to afford razors back then…

Thanks! I learned a lot while writing the post, too. I love learning about how things were back in those days! 😀

Wow, very interesting … I learned a lot! Thank you 👍❤️

👣Yvon

Thanks Yvon! I learned a lot myself! 😀

How interesting! I was pleased to see that Sweden got a mention. I shall be delving again with the article about WWI and the terrible trenches, although I know quite a lot about it, mostly from reading novels.

Yes I thought it was interesting about the Swedish steel also! Most of what I know about WW1 is from research I’ve done for family history. I also get an online newsletter called the Doughboy Foundation that has interesting articles about WW1 veterans.

👍

I think the old single blades are better than the newfangled ones they keep trying to sell.

They probably are!

I remember the old medicine cabinets in the bathroom with a slot in the back so you put your worn out blades in the slot and they drop behind the wall!

Yes! My dad had that in his!